Your weekly reading from Web Directions

This week we have a great roundup of articles across the spectrum of things that we typically pay attention to here. From design to front-end architectures, AI software engineering to accessibility, there’s plenty here to keep you engaged and thinking about what comes next, regardless of your role.

We’re also in the run home to our end-of-year conferences:

- Web Directions Developer Summit for front-end and full stack teams.

- Web Directions Next for product designers, product managers, and everyone involved in product.

- our brand new conference for WordPress developers, Equeue

The conferences all focus squarely on how AI and large language models are transforming the way we work and the products we build.

It won’t be panels with vague speculation about “the future of [fill in the blanks].” Instead it’s detailed, engaging presentations from experienced professionals sharing what they’ve actually learned building with these technologies—giving you concrete insights you can apply directly to your own work.

performance.now() coming to Conffab October 30 and 31

We’re really excited about performance.now(), the incomparable web performance conference that takes place every year in Amsterdam, coming to Confab Live. It’s great value at $249, check out the amazing lineup then register. For that you get

- access to the live stream both days

- access to the recordings on demand right after the conference ends

- and then access to our edited, enhanced individual presentations a few weeks after the conference.

Now on with the reading!

Architecture

Default Isn’t Design. Why familiar feels right but often…

Framework monoculture is a psychology problem as much as a tech problem. When one approach becomes “how things are done,” we unconsciously defend it even when standards would give us a healthier, more interoperable ecosystem. Psychologists call this reflex System Justification. Naming it helps us steer toward a standards-first future without turning the discussion into a framework war.

Source: Default Isn’t Design. Why familiar feels right but often… | by EisenbergEffect | Oct, 2025 | Medium

Frameworks, and above all React and its ecosystem, have become the most widely adopted approach to developing modern web applications. But as Rob Eisenberg observes here there are significant risks when default approaches become so entrenched. This is a detailed essay I recommend to anyone who thinks about frontend architecture. It will help question a lot of likely unexamined assumptions that we make about how we build web applications. Whatever implications it ultimately has, it will ensure that the choices we make are more informed and more conscious, and not simply the adoption of defaults.

Simplify

Honestly, I feel like web developers are constantly being gaslit into thinking that complex over-engineered solutions are the only option. When the discourse is being dominated by people invested in frameworks and libraries, all our default thinking will involve frameworks and libraries. That’s not good for users, and I don’t think it’s good for us either. Of course, the trick is knowing that the simpler solution exists. The information probably isn’t going to fall in your lap—especially when the discourse is dominated by overly-complex JavaScript.

Source: Adactio: Journal—Simplify

As I observed in a recent essay, we’ve spent the last 15 to 20 years in web development building ever more complex and complicated approaches to developing for the web. But what we often overlook is how far the web platform has come, and continues to evolve. This enables us to embrace one of the principles I articulated in my recent Dao of CSS presentation at CSS Day(watch free with no login required), of simplicity, as Jeremy Keith observes here. Jeremy looks at something that has traditionally often been implemented in very complex and complicated ways—carousels. He shows how they can be implemented with just two or three lines of CSS. Time to re-implement the video carousels on our front page, I think.

Frontend Development

The thing about contrast-color

I have to admit that I got a little over-excited when I read that the contrast-color() function is supported in Safari and was keen to try it out. But there’s a problem, the thing with contrast-color is…

Given a certain color value, contrast-color() returns either white or black, whichever produces a sharper contrast with that color. So, if we were to provide coral as the color value for a background, we can let the browser decide whether the text color is more contrasted with the background as either white or black.

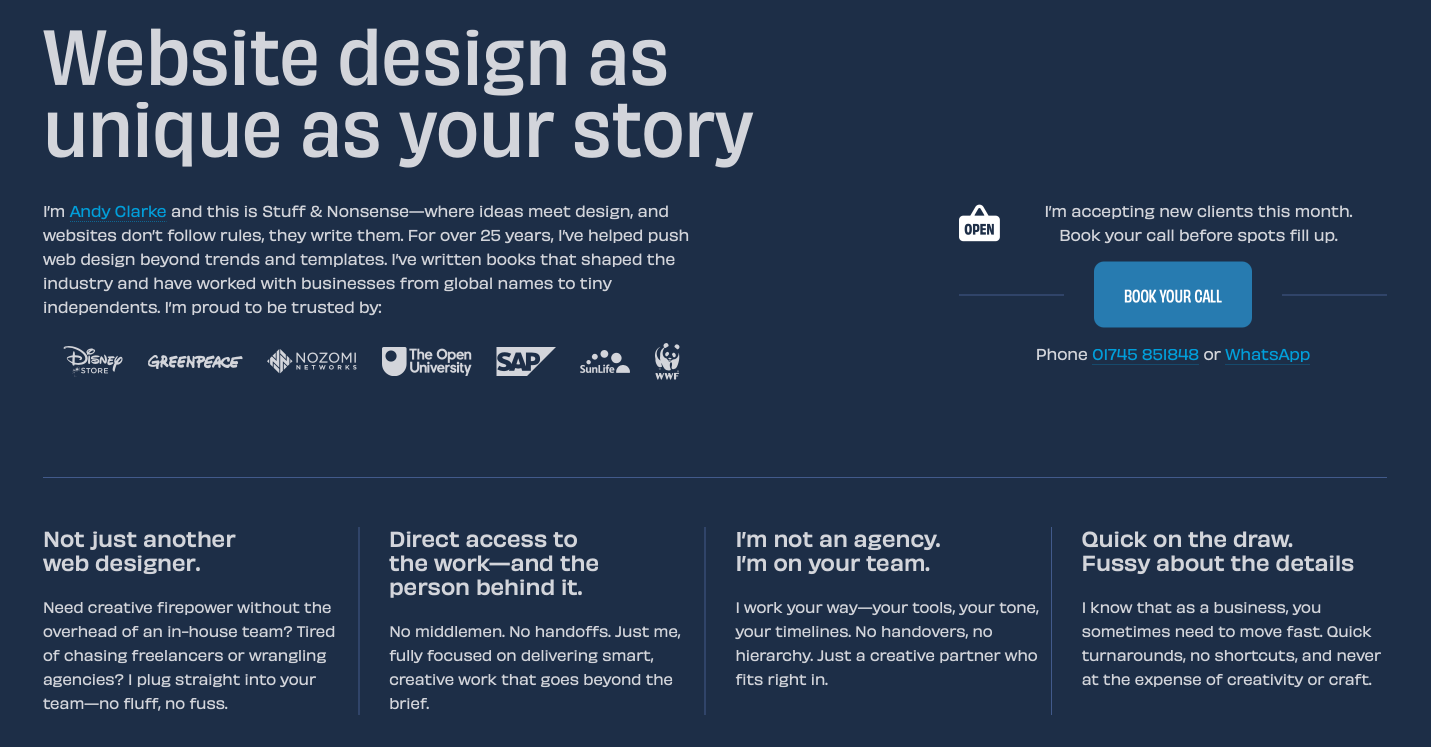

For my website design, I chose a dark blue background colour (#212E45) and light text (#d3d5da). This colour is off-white to soften the contrast between background and foreground colours, while maintaining a decent level for accessibility considerations.

Source: The thing about contrast-color • Stuff & Nonsense

We’ve covered contrast-color here recently, a relatively new CSS function that allows us to straightforwardly specify contrast in color values to ensure we have contrast. But this is relatively limited, as Andy Clarke observes in this article—define a background color and the browser will choose either black or white to contrast it with. Here Andy explores the function and how we can work with it despite this apparent limitation.

CSS :is() :where() the Magic Happens

CSS CSS Architecture Selectors

For Blogtober, I dug up a draft about the two CSS pseudo-class functions :is() and :where() that I’d had lying around in my drafts folder for quite some time. Actually, when I originally started writing this post, :is() and :where() had just landed in CSS, and—just like with so many other new CSS features—I was expecting them to “change the way we write CSS.” Both are now widely available baseline features supported by all modern browsers.

Source: CSS :is() :where() the Magic Happens · Matthias Ott

Matthias Ott looks at two relatively new CSS selectors that are now widely supported and how they are being used in the wild as well as how you might best take advantage of them.

A pragmatic guide to modern CSS colours – part one

For most developers, the only time they touch colour values is when they copy them from a design file and paste them into their editor. We are developers and not designers, after all. However, there have been a lot changes to colours in CSS over the last few years—from updates to the syntax of familiar features to all new ways of working with colours—that even copy/pasters can take advantage of.

Source: A pragmatic guide to modern CSS colours – part one – Piccalilli

We’ve been covering color in terms of CSS quite a bit lately, which I think reflects how much is happening and how much interest there is in this. Here’s the first part of a multi-part series on modern color in CSS.

Big O

Algorithms Computer Science Performance

Big O notation is a way of describing the performance of a function without using time. Rather than timing a function from start to finish, big O describes how the time grows as the input size increases. It is used to help understand how programs will perform across a range of inputs. In this post I’m going to cover 4 frequently-used categories of big O notation: constant, logarithmic, linear, and quadratic. Don’t worry if these words mean nothing to you right now. I’m going to talk about them in detail, as well as visualise them, throughout this post.

Source: Big O

I remember first being introduced to Big O notation most likely in my first year of computer science, decades ago now. As someone who’d fiddled around with programming in languages like BASIC, it likely never occurred to me that programming was a kind of mathematical science and we could reason about it in the same way we reason about things like mathematics. Big O notation is a way of thinking about the performance of an algorithm in relative terms. This is a great, dynamic, and engaging exploration of the topic.

HTML—the Most Difficult Programming Language in the World

Years ago, the web development community discussed and declared on Twitter that HTML was not just a document language, but a programming language. Meanwhile, virtually no HTML page is error-free. In HTML parlance, almost no page is conformant, compliant, valid, or “validates.” (Cf. validation data from 2021 through 2025.)

Source: HTML—the Most Difficult Programming Language in the World · Jens Oliver Meiert

It’s a relatively simple syllogism: 1. HTML is a programming language (as many believe, certainly I do). 2. Essentially, no HTML document is without errors. 3. Therefore, HTML is the most difficult programming language in the world.

AI & Software Engineering

Just Talk To It – the no-bs Way of Agentic Engineering

AI Native Dev LLMs Software Engineering

I’ve been more quiet here lately as I’m knee-deep working on my latest project. Agentic engineering has become so good that it now writes pretty much 100% of my code. And yet I see so many folks trying to solve issues and generating these elaborated charades instead of getting sh*t done.

Source: Just Talk To It – the no-bs Way of Agentic Engineering | Peter Steinberger

When I very first started developing software in any serious kind of way at university in the mid-1980s, waterfall was only then starting to become a standardized practice. Before then, particularly at the scale of architecture, there really weren’t any established practices to speak of. We’ve since seen the Agile revolution, but it seems clear that we’re in the midst of a similar revolutionary transformation in how we develop large-scale and small-scale software products. We’ve published a few of these accounts so far where experienced developers talk about how they are working with large language models as software engineers. It’s fascinating to see how different engineers work with these technologies, what they are learning, how their process is iterating and evolving, and how it compares with other very experienced developers. Are we evolving towards the one true way we should work with these models? Or do different use cases require different processes? Or do different models work better with different approaches? None of that is clear, but it’s definitely interesting to get these sorts of inputs into our own decision-making about how we should be working with the models.

The Programmer Identity Crisis

AI Native Dev LLMs Software Engineering

In fact, if we are to trust the billion-dollar AI industry, the denizens of Hacker News (and its overlords), and the LinkedIn legions of LLM lunatics, the future of software development has little resemblance to programming. Vibe-coding—what seemed like a meme a year ago—is becoming a mainstay. Presently (though this changes constantly), the court of vibe fanatics would have us write specifications in Markdown instead of code. Gone is the deep engagement and the depth of craft we are so fluent in: time spent in the corners of codebases, solving puzzles, and uncovering well-kept secrets. Instead, we are to embrace scattered cognition and context switching between a swarm of Agents that are doing our thinking for us. Creative puzzle-solving is left to the machines, and we become mere operators disassociated from our craft.

Source: The Programmer Identity Crisis ❈ Simon Højberg ❈ Principal Frontend Engineer

The author’s use of “craft” and “identity” here really crystallizes something I’ve been thinking about: many software developers have built their sense of self-worth around writing code itself, rather than around solving problems or building products. When that activity feels threatened, an existential anxiety is palpable. I’ve come to realize—though it took me decades—that I was never really interested in producing lines of code per se. I’m interested in building products and solving problems. The code is a means to that end. I think the distinction between systems engineering (where every line of code, every character indeed matters from the perspective of performance and security) and product engineering (where code is a tool to solve user problems) has only recently become clear, though I don’t think we in general recognize it. What troubles me about the tenor of these conversations is the dismissive language—terms like “slop-jockey” deployed with obvious contempt. I see this frequently, even from people I’ve traditionally respected. It makes good-faith engagement nearly impossible. If we can’t discuss these changes without resorting to sneering dismissal of people who work differently than we do, we’re not having a conversation about the future of software development—we’re just protecting our identities. The question isn’t whether AI tools change how we work. They do. At least in many contexts and situations. The question is whether our value as software professionals was ever really about the typing, or about something else entirely.

Australia’s AI choice: Standards setter or technology taker?

AI is not born neutral. The rules that govern how it behaves are set by its authors: corporations and governments embedding their own assumptions, priorities, and cultural defaults into code. Those rules travel with the system. If Australia adopts AI built to foreign specifications, we also import those embedded choices—about privacy, bias, autonomy, and control. We can avoid this dependency only by setting our own AI development guidelines, explicitly crafted to preserve sovereignty. That means writing the governance rules here, not just buying in systems and pretending we can retrofit “Australian values” later. The strategic choice is not whether to use AI, but whether to use someone else’s rules or our own.

Source: Australia’s AI choice: Standards setter or technology taker? | Lowy Institute

Will large language models, particularly the largest frontier models, be restricted to a handful of the largest, best-resourced labs in the world, closely associated with the largest, most powerful nations in the world, like the United States and China? Or should other nations like Australia invest in their own sovereign models? Here Ian Gribble explores the implications for a nation like Australia of the increasing importance of AI and large language models in the modern world.

Design

Designing Amiable Web Spaces: Lessons from Vienna’s Café Culture

Today’s web is not always an amiable place. Sites greet you with a popover that demands assent to their cookie policy, and leave you with Taboola ads promising “One Weird Trick!” to cure your ailments. Social media sites are tuned for engagement, and few things are more engaging than a fight. Today it seems that people want to quarrel; I have seen flame wars among birders.

These tensions are often at odds with a site’s goals. If we are providing support and advice to customers, we don’t want those customers to wrangle with each other. If we offer news about the latest research, we want readers to feel at ease; if we promote upcoming marches, we want our core supporters to feel comfortable and we want curious newcomers to feel welcome.

In a study for a conference on the History of the Web, I looked to the origins of Computer Science in Vienna (1928-1934) for a case study of the importance of amiability in a research community and the disastrous consequences of its loss. That story has interesting implications for web environments that promote amiable interaction among disparate, difficult (and sometimes disagreeable) people.

Source: Designing Amiable Web Spaces: Lessons from Vienna’s Café Culture

I’m a sucker for drawing lessons from historical periods, maybe those that have been overlooked or somewhat forgotten. I’m also a bit of a sucker for sitting around in cafes and having pleasant conversations. This article on A List Apart, which draws lessons from Vienna’s cafe culture of the interwar years (the first part of the 20th century), really caught my attention. It’s often observed that things that make folks angry are the things that get more clicks, and in a click-driven, attention-scarce, advertising world, it’s no surprise we often get content and experiences that one wouldn’t characterize as amiable. And yet, do people really want to live in a world driven by anxiety, conflict, contradiction, and argument? Take a moment to draw some lessons from a more civilized time and space. One that ironically ended very soon after in one of the worst episodes of human history.

Where’s the AI design renaissance?

I create and sell online design courses for many folks in tech—designers, aspiring designers, design-adjacent—and one question I’ve gotten a lot over the last two and a half years is: what is AI going to do to design?

I’ve been hesitant to answer too confidently, since things have been moving very quickly, and—as a teacher of design—I fall straight into a trap put so memorably by Upton Sinclair a century ago:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

― Upton SinclairThat being said, if the robots are taking all the design jobs any time soon, I also would like to find my next act. So you can take this article with a grain of salt, and feel free to push back in the comments, on X, or via email. This post attempts to answer two questions: Will AI take design jobs? If so, which ones? In light of that, what should designers focus on?

Source: Where’s the AI design renaissance?

If AI is radically transforming fields such as design, where is the actual impact and the benefit? After nearly three years of the ChatGPT world Erik Kennedy asks, where is the AI design renaissance? It’s a really thoughtful essay. I really recommend. It starts from a place of humility, which I think is a very good place to start when it comes to thinking about these technologies.

Accessibility

Annotating designs using common language

In most organisations, design documentation often includes annotations, but accessibility-specific ones are still rare. That’s a missed opportunity. Annotating designs for accessibility helps everyone involved understand what needs to be built, tested, and maintained.

Using a common language that designers, developers, and quality assurance (QA) teams all understand is essential so that information doesn’t get lost in translation, especially during the hand-off between design and development.

Source: Annotating designs using common language – TetraLogical

Craig Abbott from TetraLogical explores the use of design annotations specifically around accessibility.

Web Performance

The History of Core Web Vitals

Core Web Vitals measure user experience by assessing a website’s performance. This write-up is a history of how Core Web Vitals came to be based on my recollections from our work on it at Google from 2014 onwards. The initiative saved Chrome users over 30,000 years waiting with businesses seeing revenue and user-engagement lifts through optimizing for it, inclusive of 2025.

Source: AddyOsmani.com – The History of Core Web Vitals

Addy Osmani, who was involved from the early days in the development of what became Core Web Vitals, charts its history and its impact.

Great reading, every weekend.

We round up the best writing about the web and send it your way each Friday.