The end of social media, and naive optimism

Way back in 2008 or 2009 (maybe even earlier) we first started using Twitter in association with our conferences. We’d encourage folks to tweet with associated hashtags, and had big tweet walls, built our own aggregators–and were a globally trending tag a couple of times. Hundreds of people would tweet thousands of times collectively at events back then. ‘Official hashtags’ were a thing.

That has slowly faded over time, but this year while there was plenty of Linkedin and mastodon engagement, very little Twitter engagement.

In the last few weeks I have finally weaned myself off Twitter, something I was an early adopter of and advocate for. Something I’ve posted tens of thousands of times to.

Now I take look every few days to see I haven’t missed a direct message or some reference to me or the conferences that needs addressing. That will slowly fade over time to nothing I expect.

I feel I’m definitely the better for it. When occasionally the old muscle memory kicks in and I visit, I immediately feel a sort of queasiness.

I use LinkedIn professionally, sometimes posting, reposting, but nothing like the frequency of how I used Twitter. Nor the honesty-LinkedIn is buttoned down professional John–I never kept the professional and personal separate on Twitter.

I joined Mastodon a bit over a year ago but only recently has it become a habit not unlike (but not as strong as) Twitter was.

As many who were early Twitter users have observed, it has qualities of a time on Twitter before folks had worked out how to game it for attention, when it was largely people you knew, or who knew people you knew. When we thought connecting up all the people from all over the world. Where users contributed to the platform–improvising patterns like the hashtag, building all manner of apps that consumed the then free (now tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for pretty much any use) easy to use API.

But the commons was long ago enclosed. Twitter’s slow demise, accelerating over the last year (hmm, I wonder why?) now seems almost inevitable. But whatever magic it one conjured from the collective behaviour of its users has long gone.

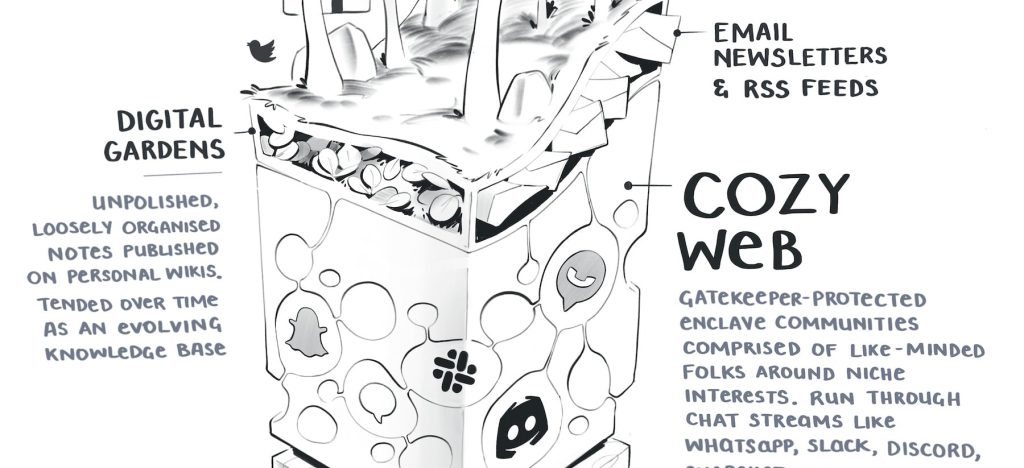

Indeed, it’s quite possible an era of mass collective social media is over. As Maggie Appleton observed during her absolutely stellar keynote at Web Directions Summit last week, we’re likely to retreat to the ‘cozy web’–

Gatekeeper-protected enclave communities comprised of like-minded folks around niche interests. Run through chat streams like WhatsApp, Slack, Discord, Snapchat, etc

The Expanding Dark Forest and Generative AI

In those heady days when social media, like Twitter (and at that time to lesser extent Facebook, then Instagram) were emerging, I was far from alone in my optimism–that by connecting everyone, we’d collectively address the pressing, collective challenges of our time. We’d see each other for what we had in common.

Oh man were we naive.

So when I took the stage last week to kick off Web Directions, which began (in a slightly different guise) way back in 2004, before modern social media, I reflected on how we find ourselves at a time, not unlike then, of accelerating change–back then due to the increasingly widespread adoption of the web, this time brought about by the emergence of generative AI.

I’m not without my optimism for the prospect and possibility these technologies represent. But that is very much tempered by the experience of the last 30 years of the Web.

The Web, something generously given to the world, by its creators–’this is for everyone’ as Tim Berners-Lee, principle among those creators Tweeted (quite the irony) at the London Olympics opening ceremony.

The Web, a literal commons, enclosed by the technology giants, who took that which we created collectively, billions of documents, billions of social posts, billions of photos and videos, freely shared advice and wisdom and expertise, built gates around those commons, extracted their value, for their own staggering enrichment, and in Cory Doctorow’s telling neologism ‘enshittified’ them.

An attendee at Web Directions very politely communicated during one of the breaks that they felt the keynotes at Web Directions this year were a little pessimistic. I agree. They meant it as a kind of criticism of sorts, something they felt was misplaced–shouldn’t we be optimistic at what AI can deliver? Their heart was certainly in the right place. Yes, technology could make our world better–gains in productivity could deliver more leisure time, just as we’ve been promised for decades (in primary school in the 1970s I distinctly recall how one of the dilemmas of our future was what to do with all the leisure time that was coming our way as machines removed the necessity to work as much).

But I don’t think our keynote speakers’ pessimism was misplaced. Not given their experience and track records, unearned.

In 2006 the optimism was naive, but perhaps that time it would be different–Google, Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, these were all still nascent or new, run by people who made their company mottos things like ‘Don’t be evil’ (a pretty low bar in retrospect).

Now, after how the last 20 years have played out, anyone thinking in unbridled techno-optimistic terms is either so profoundly privileged as to be entirely immunised from the negative impacts of technology, or deeply naive.

And yet I still, like those keynote speakers, have a belief in the promise of technology, but technologies are things we create and make choices about. Individually, as societies, and as civilisations. Those choices might seem opaque at times, but they are rarely accidents.

And once those choices are made, the implications are very long lasting. How we are going to use generative AI. How, or even whether, we acknowledge and compensate the work of countless writers, artists, developers, and others whose words, code, music and art are the raw material without which the large language models cannot exist is a choice. To whom the productivity benefits of these technologies accrues is a choice.

These are choices we can’t simply wave away with vague references to rising technological tides lifting all boats, loose historical analogies to the ultimate positive aspects of the industrial revolution and the backwardness of the luddites. We have to think more rigorously than that.

Because the choices we make now will shape decades. And naive optimism really wasn’t a great approach last time we were here.

Great reading, every weekend.

We round up the best writing about the web and send it your way each Friday.